The geopolitics of Kazakhstan

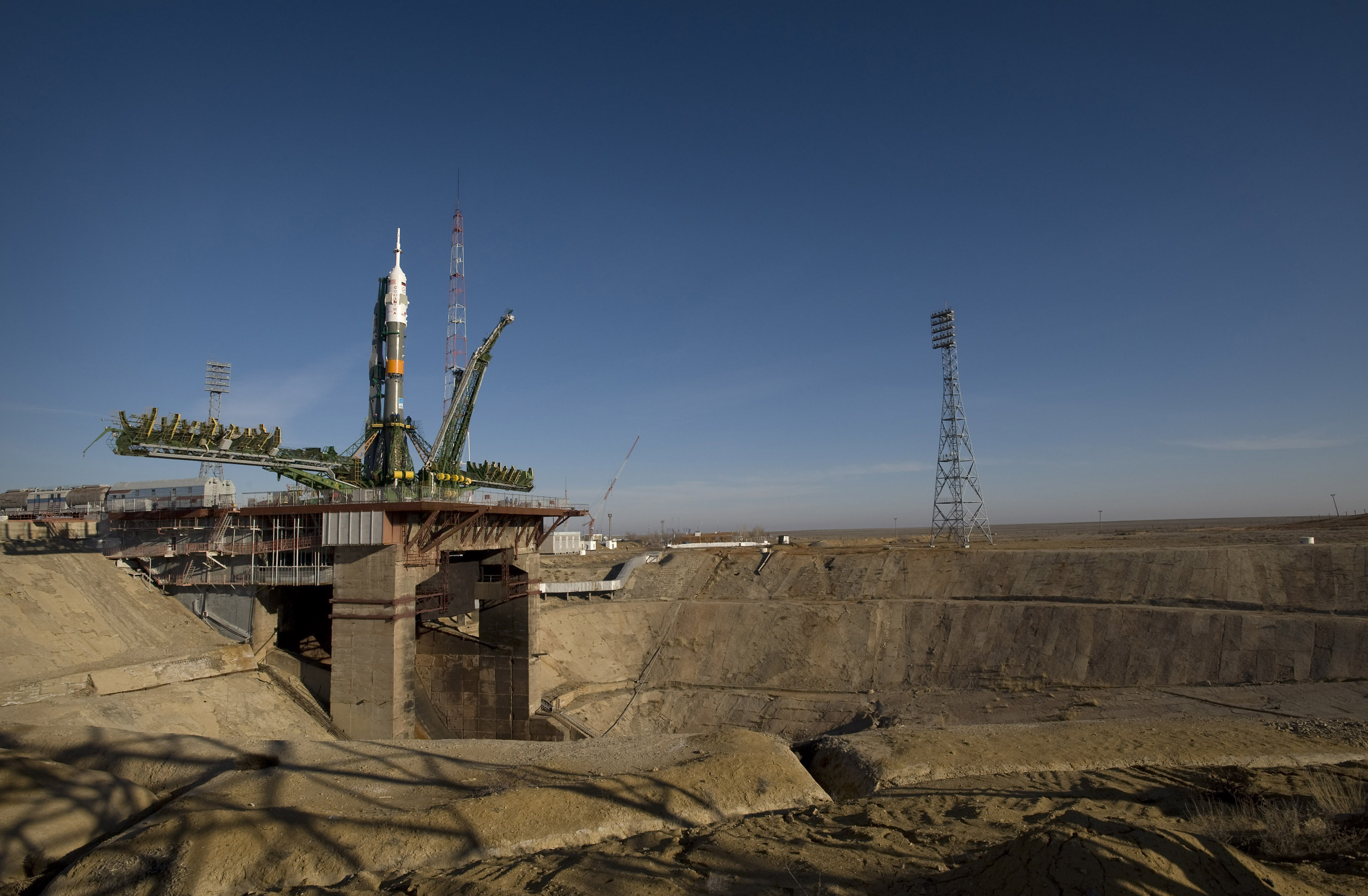

The Soyuz rocket at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan (NASA/Bill Ingalls, commons.wikimedia.com)

A country with enormous geopolitical potential, but with an economy unable to put it to good use, and a foreign policy that is too subordinate to Russia. Kazakhstan’s weakness as well as its extraordinary mineral wealth and strategic location risk fueling Moscow’s appetites for this vast region of the former Soviet Union, while China stands ready to defend its strategic interests connected to the Belt and Road Initiative. The recent riots show a general disaffection of the population towards the ruling class, which has built the national institutions on a family model, precisely around the family of the previous president. The Kazakh republic apparently suffers the resource curse, that is, that phenomenon that happens in countries with an abundance of natural resources, less democracy, or worse development outcomes than countries with fewer natural resources. Europe could play a significant role to help the central Asian country modernize its political institutions, economic infrastructures, and societal organizations. After the Russian Federation and China, Italy is the country’s largest trading partner, while Switzerland is the sixth.

Kazakhstan’s commodities-dependent economy has been suffering since 2014 when oil and minerals prices crashed. In just three years gross domestic product dropped by 42% from 235.6 in 2014 to 137.3 US$ billion in 2016.[1] A modest recovery followed because of a surge in commodities demand, but the precrisis level of wealth have not yet been reached.

In 2019, KPMG, a consultancy, calculated that Kazakhstan’s 0.001% of the population, or 162 persons, are worth more than US$ 50 million, which equates to around 55% of the total wealth of the population,[2] many of those are connected to the former presidentNursultan Nazarbayev by blood or business dealings.

Some analysts, such as The Economist Intelligence Unit, has consistently classified Kazakhstan as an autocracy,[3] others as one of the strongest examples of a modern kleptocracy, as Thomas Mayne, an expert in corruption studies and Central Asian politics, described it.[4]

The worsening economic condition in the country has exacerbated discontent to which the pandemic has added more strain. Since 2014 prices have galloped at an average inflation rate of 7.63% with a peak of 14.55% in 2016,[5] wealth gap has widened by 3%,[6]and the state has apparently failed to help the most vulnerable in an adequate way. Although Nazarbayev’s administration hired well-paid consultants, including Tony Blair Associates, an umbrella organization established by the former UK prime minister, for advice on building a positive image at home and abroad, their methods may have offered superficially attractive but shallow solutions to complex problems of economic inequality, social mobility and political aspirations.

On 2 January 2022, after a sudden sharp increase in the price of liquefied petroleum gas, locally the motor fuel of choice, since there is no popular opposition group against the Kazakh government, a few hundred demonstrators directly assembled to protest in the oil-producing town of Zhanaozen, a national byword for human rights abuse after police killed 14 oil workers protesting over labor rights in 2011.

The unrest quickly spread to other towns in the country, especially the nation’s largest town Almaty, fueled by rising dissatisfaction with the government and economic inequality. The incumbent president Kassym-Jomart Tokayev declared a state of emergency in the whole country. In response, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) – a military alliance of Russia, Armenia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan itself – agreed for the first time since its establishment the deployment of peacekeeping troops in Kazakhstan.

During the week-long violent unrest and crackdowns, 164 people were killed, more than 1,000 were injured, and over 9,900 were arrested. The toll death is likely to be a major underestimate as government-imposed internet blackouts largely blocked independent and social media, which allowed president Tokayev to tell only his narrative about the protests.

Without providing evidence, president Tokayev accused foreign powers of stirring unrest. He claimed – sic et simpliciter – the protests were taken over by religious radicals, criminal elements, out-and-out bandits, poachers and small-time hooligans. Within few days, president Tokayev duly sacked his cabinet, reversed the fuel price rise and removed Nazarbayev as head of the powerful Security Council. The unrest in the central Asian republic could be, indeed, a power struggle among domestic elites, particularly against Nazarbayev, who served as president for three decades until 2019, and his family from their behind-the-scenes positions of power.

Kazakhstan’s president appeal to a Russian-led military alliance for help has made the political scenario even more combustible, as it may generate bigger backlash. The reliance on Russian support to cling on to power dilutes Kazakhstan’s sovereignty. It bolsters Putin’s key objective of rebuilding Russia’s sphere of influence. Moscow could use this as a pretext to take back northern Kazakhstan, home to a large ethnic Russian community, precisely 20% of the total Kazakhstani population. Indeed, the potential for regional secession may have motivated the Kazakh government’s 1997 decision to move the country’s capital from the southern town of Almaty to Astana, recently renamed Nur-Sultan, far closer to the country’s northern stretches.

Furthermore, Kazakhstan is a big oil producer and member of the Opec+ group of countries. According to the World Nuclear Association in London, Kazakhstan is the world’s biggest producer of uranium as it accounts for more than 40 per cent of global primary production,[7] and it is among the top ten suppliers of zinc[8] and copper[9]. Not less importantly for the Kremlin, its Baikonur Cosmodrome, built by the USSR Ministry of Defense in 1955, it is still the world’s first spaceport for orbital and human launches and the largest in operational space launch facility from where every crewed Russian spaceflight is launched.

A lot remains murky in the future of Kazakhstan, clouds are looming on the steppe, the question naturally arises of what the geopolitical power of Kazakhstan is, and, more precisely, in respect of Russia.

Geopolitics, although it is a rather popular discipline today, often used even in contexts where it has little or nothing to do, still lacks a univocal and shared definition.

Before trying to define the geopolitical power of Kazakhstan, perhaps it is convenient to try, without too much ambition, a factual definition of geopolitics such as that discipline that studies international relations in a geographical key, more precisely the expansionist or, more modestly, influential aims of a state in operation of i) its spatial position in the sense not merely geographic, but also economic, military and ethnic, ii) its accessibility to natural resources, industries, markets, sea and land routes, with particular reference to neighboring countries.

Kazakhstan, literally the land of the wanderers, is a massive landlocked country – three time zones –, equal to the size of Western Europe, dwarfing the other former Soviet republics of Central Asia in terms of land mass, with a border of 6,846 kilometers with Russia, which is second only to the US-Canada border, and of 1,533 kilometers with China.

With barely 19 million people, Kazakhstan has one of the lowest population densities in the world, factually a bunch of people that occupy a boundless territory in two continents, of which in every ten, approximately seven are Kazakhstani, two Russian and one ethnically belonging to some neighboring country.

Placed between Russia and China as well as Iran and Turkey, Kazakhstan is factually at the center of large flows of people and goods, including oil and gas transit, which may provide it with a first geopolitical weight across the region.

The sea routes are not safe enough for the Beijing administration as the influence of the USA and their allies in the Pacific is increasing, the problems over Taiwan are getting thornier, and the competition in the Arctic is intensifying. In 2013, China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and not by coincidence, it gave Kazakhstan an important role as a transit hub and a safer land corridor, which increased its role in global trade to open its markets to billions of people. China is the main economic and trade partners of Kazakhstan after the Russian Federation.[10]

Being just a movement of caravans across the steppe can make Kazakhstan rely on a substantial external rent with little development of a strong domestic productive sector as well as only a small proportion of the working population can be involved in the generation of the rent, and, more alarming, the state’s government becomes the principal recipient of the external rent.

According to the Oil & Gas Journal (OGJ), Kazakhstan has proved crude oil reserves of 30 billion barrels, the second largest endowment in Eurasia after Russia, and the twelfth largest in the world, just behind the United States,[11] equal to 1.8% of the world total,[12] which may provide Kazakhstan with a second geopolitical weight in the region.

There are, though, only three refineries within the country, which are not capable of processing the total crude output, so much of it is exported to Russia without adding any substantial value. In addition, Kazakhstan is landlocked, at long distance from international oil markets, and the lack of access to the open ocean makes the country dependent mainly on pipelines to transport its hydrocarbons to world markets.

Along with oil, Kazakhstan’s great good fortune is to be found beneath its soil, as it is rich in uranium and other metals such as chromium, lead, zinc, manganese, copper, iron and gold. These natural treasures make a difference only if the country owns or develops a downstream industry and supply chain capable of adding value to lamps of oxides to be transformed in finished products with innovative technological content and high-quality, otherwise it can turn to be a resource curse.

By leveraging on its two main geopolitical weights, that is, its spatial position and accessibility to primary natural resources, over the last decades, since Kazakhstan became independent from the USSR, it has followed a multivector foreign policy, that is a policy that develops foreign relations through a framework based on a pragmatic, non-ideological foundation, more precisely, the development of friendly and predictable relations with any state that plays a significant role in world affairs and is of practical interest to the country.

An approach that disregards ideological calculations favoring the pursuit of state’s interests may work until to the regional great powers – namely Russia and to some extent China – are paid homage, their requests are granted, or loyalty is kept. If it may happen that the bear wakes up from hibernation, or the dragon has a tantrum, then the question can get serious.

A country is considered powerful if it has a strong economy, a large military, a smart population. This power can be defined as national industrial strength, technological advance, military might, educational level and size of the population. Futhermore, a foreign policy with no ideological foundation is tactics not strategy.

Can Kazakhstani population defend their country from an invasion? Can a population of 19 million people of which about 4 million ethnically Russian repeal an attack coming from a border of thousand kilometers? Can an army ranked 64th for global firepower deploy sufficient forces on its immense territory?[13] Can a country rich in oil and other fossil fuels but distant from the largest markets dictate its own rules? Can a country be laying on vast minerals deposits but with a poor processing industry influence world’s market price? Can a transit country with no or little added value to the flowing goods be irreplaceable? The answer is simply negative: the geopolitical power of Kazakhstan is weak.

The artificiality of USSR’s borders as well the Kazakhstan’s ethnic-demographic composition carries a quite hypothetical but real threat to Kazakhstan’s territorial unity. Economic interweaving between the two countries is considerable. Of the 14 Kazakh administrative regions seven front onto Russia. The entry of Russian troops in Kazakhstan may reveal the end of an already-frail independence, Tokayev’s move may turn to be fatal. When the Russian army sets a foot on a piece of land, particularly if it was part of the former USSR, it is then hard that the Russian leave the occupied territory. Three recent experiences, the first, Georgia’s Abkhazia region, that Russia invaded in 2008, the second and third, Ukraine’s Crimea and Donbass regions that Russia invaded in 2014, show clearly the expansionistic ambitions of the former intelligence officer Vladimir Putin.

On the easter border Xi Jinping’s China would not stay and watch. Beijing may bring in its army to defend its own economic and political interests, above all its direct investments in Kazakh-Chinese projects worth US$ 27.6 billion that cover various industries, such as metallurgy, oil and gas processing, chemistry, machine building, energy, transportation, production of building materials and agribusiness as to secure its energy and raw materials requirements.[14]

The European Union might consider a famous Italian proverb that says between two litigants the bystander enjoys. It is never too late.

This article was firstly published online in English on Aspenia Online on January 17, 2022, and later in Italian on printed paper in Aspenia Rivista issue 96 on March 22, 2022.

References: [1] Kazakhstan, GDP (current US$), The World Bank, retrieved January 2022; [2] Private equity market in Kazakhstan, KPMG, May 2019; [3] Global democracy index 2020, The Economist, 2 February 2021; [4] Researching kleptocracy in Eurasia, Eurasianet, 4 June 2021; [5] Kazakhstan, inflation, consumer prices (annual %), The World Bank, retrieved January 2022; [6] Kazakhstan, Gini index, The World Bank, retrieved January 2022; [7] World uranium mining production, World Uranium Association, updated September 2021; [8] Mineral Commodity Summaries, Zinc, U.S. Geological Survey, January 2021; [9] Mineral Commodity Summaries, Copper, U.S. Geological Survey, January 2021; [10] Kazakhstan, World Integrated Trade Solution, The World Bank, 2019; [11] Kazakhstan, U.S. Energy Information Administration, last updated 7 June 2019; [12] These 15 countries, as home to largest reserves, control the world’s oil, USA Today, 22 May 2019; [13] 2022 Military strength ranking, Global Firepower, last retrieved January 2022; [14] Construction of Kazakh-Chinese investment projects will be carried out in accordance with the legislation of Kazakhstan, Kazakh Invest, 10 September 2019.